“It’s like racism or sexism, you have to pull these things out. It’s like a tooth that’s festering, until you say it’s infected, until you name it, it goes on hurting.” Jeanne Sarson

Linda MacDonald and Jeanne Sarson are two nurses from Truro, Nova Scotia. In their spare time, they offer counseling services to women. It was in this context that they met with and became dedicated to victims of hidden and organized extreme violence. Their professional advocacy for these marginalized women expanded into political activism, and after two decades, their successes on the global stage are yet unmatched. Indeed, they inhabit a sphere and path entirely of their own making. It all began over twenty years ago with a late night phone call.

Jeanne explains, “Our work began when I answered my business phone one night at about 11:15 p.m. I was aware that I was thinking several things. Firstly, that it made no sense for me to answer my phone so late at night as Linda and I did not provide this kind of late-night support, but, at the same time, I had an intuitive sense that it was essential to pick up the phone. So I answered it. The voice I heard was that of a woman I did not know saying she was planning to commit suicide in four days. I had no way of contacting her so we talked. In the end she agreed to call back the next night.

“At about the same time of night, as on the previous evening, I received her second call. From this call she agreed to meet with Linda and I out-of-doors near her car so she felt safe. She then agreed to meet in-doors in our rented office space. Witnessing her terror and listening to her, we realized she was disclosing torture victimization perpetrated and organized firstly within the family unit and secondly her victimization was also organized and connected to like-minded other perpetrators. Thirdly, she recounted being still victimized by health care providers and therefore would not accept any support that would come from mental health institutional clinics. Unable to find other sources of support for her we decided we could not abandon her. Thus, we informed her that although we did not have training in torture recovery and rehabilitation, we would try to help.” The year was 1993.

Speaking in hindsight, Jeanne uses descriptive words like “torture victimization” to explain what Sara had related to her and Linda, but it would be several years after that meeting before the pair’s language would evolve into what it is now. The experiences that Sara shared were, at the time and often still, referred to as ritual abuse. Ritual abuse is a clunky, evasive phrase. How does one abuse a ritual? Is the context, or an aspect, of an act of violence more important than the violent act itself? Ritual abuse is also the target of 20-year-long disinformation campaign so successful that most people believe it doesn’t exist.

Linda and Jeanne were the first to expand the phrase to Ritual Abuse-Torture. Jeanne says, “As soon as we began listening to Sara, we realized we were listening to torture victimization; we never referred to the violence she was disclosing as ‘ritual abuse’ in the way ritual abuse has been described. We asked Sara for her opinion. She thought she had endured torture thus the term of ritual abuse-torture immediately fell into place as being truthfully respectful of the violence she described enduring.

Amnesty International defines torture as “the systematic and deliberate infliction of acute pain by one person on another, or on a third person, in order to accomplish the purpose of the former against the will of the latter.”

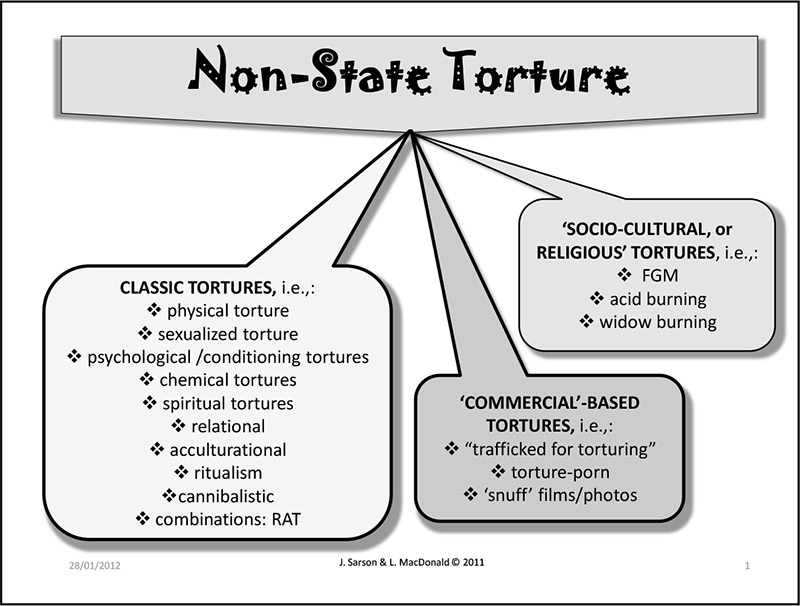

In 2004, to help bring to light the plight of Sara and others whom they’d counseled and interviewed (eventually numbering in the thousands), Linda and Jeanne began presenting at the meetings of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW). There they encountered women who’d suffered similar violence but in different contexts, not necessarily involving ritual. This awareness, combined with their increasing expertise on legal definitions and the language of human rights, led them to broaden their conceptual framework. Linda says, “We listened to a woman for two years detail how she had been held captive, tortured, and trafficked by her husband and three of his friends. We realized then that we had to adopt a more generalized perspective about torture victimization that was perpetrated by private individuals/groups.”

Torture is prohibited by several conventions in international law. Article 5 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states: “No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” However, most applicable legal definitions of torture are restricted in scope. The UN Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, adopted in 1984, specifically addresses it as a tool of States, carried out with the intention of obtaining information. But what about torture that is inflicted for other purposes and by people who are not acting on behalf of a government? With few exceptions (Australia, France, Michigan US, California US), there are no domestic legal prohibitions against these crimes. Torture that is not carried out by States is currently prosecuted under more common statutory offenses such as assault, rape, or kidnapping.

Linda and Jeanne believe these categories fail to describe and address the severity of the acts and their impact on victims. Since women and children make up the majority of victims of torture in the private sphere, they see this as yet another form of gender discrimination—happening on a global scale. “From our feminist perspective, we know that naming clearly and accurately the human right crime one has endured is essential to feeling one is being heard, being understood, and gaining a sense of restoring one’s dignity. Also, from our feminist perspective, healing is helped when patriarchal discrimination, oppression, and violence from a gendered perspective is understood. Therefore, to invisibilize the reality that some women and girls suffer degrees of violence that constitute torture by misnaming it as another human right violation and crime was a position we were unwilling to take.

Where is the line between abuse and torture? Linda says, “It’s the powerlessness involved, it’s the continuousness of it, it’s the level of cruelty.” Acts carried out by the state, such as electric shock, forced drugging, and water boarding are clearly labelled torture, not abuse, so that same line should be drawn in a non-State context.

An essential key to defining the line is intention. Linda explains, “In abuse, the goal is to control a person. In torture, the intentionality is to destroy the sense of self of the person.” This is dissociation. “We know that soldiers who’ve endured torture, even if they didn’t dissociate as children, they’ll become dissociative as adults.” The same is true for women, yet the symptoms of dissociation, as well as other normal responses to extreme violence, are often invoked in rationalizations to disbelieve or discredit the victim. This is the insult to injury most survivors face. Jeanne says, “When people talk about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, we say no, we disagree, you might have traumatic stress responses, but we are unwilling to say you have a disorder. What are people expecting of someone who withstands torture, to come out of it laughing? That’s the insanity of calling these responses a disorder.”

The current literature on surviving violence is peppered with phrases such as organized abuse, extreme abuse, extreme trauma, as well as the old standard ritual abuse, all used to describe what are essentially the same violent acts and criminal scenarios. Jeanne is careful to point out that “extreme” means at the far end, and that means torture. Additionally, “If you use the word ‘trauma’, it is still not naming the human rights violation. It’s torture. If everyone is using the same language, you get more of a collective voice. It’s respectful to the suffering.”

Clearly what’s needed is for survivors, advocates, and caregivers to come together to craft the language of that collective voice, to re-contextualize what we’ve endured and witnessed in terms of crime and violations of human rights, and to move the discussion away from endless examinations of our symptoms. Such clarity should be more effective in influencing societal denial, and eventually, the responses of social service and justice institutions. Ultimately, that is what Linda and Jeanne hope to accomplish, the recognition by States of non-State torture and the enactment of domestic legal prohibitions against it.

Twenty one years after meeting Sara, they are closer to that goal than ever before. In November, they came away from the Geneva NGO Forum Beijing+20 at the United Nations in Switzerland with a significant victory—a formal recommendation. It reads: “(2.h.) All States must ensure national laws criminalize non-State torture perpetrated by non-State actors and that laws prohibit and hold perpetrators accountable for gender based non-State torture crimes.” They say there are ripple effects already: dozens of activists from around the world returning to their home countries prepared to lobby their governments for legislation on non-State torture; a child advocate from France who came away with a new way of perceiving the experiences of the children in her care, and a new approach to helping them; a Canadian survivor who for first time in her life heard an accurate name for what she’d endured, and finally felt validated.

Back home in Canada, the CBC named its coverage of Linda and Jeanne’s work on defining non-State torture among the top 10 stories of 2014. Listen to the half hour long radio documentary, which begins, fittingly, with Sara.

…

Find extensive information about non-State torture on Linda and Jeanne’s website: http://nonstatetorture.org

Join the conversation!

Share your reactions, stories, and ideas on the importance of naming, and help to shape our collective voice.

Keep up the global groundbreaking ladies, you are an inspiration!

Thank you Lynn for your very searching questions followed by our interview which gave Linda and I the opportunity to share our thoughts and perspectives with you. Lynn, I apologize for my delay in sending you my respect for the work you have done in writing the article; I am just now able to get to my computer since yesterday. Lynn, may you have future success in all that you undertake in Borne.

Thank you Jeanne!

Excellent article, reblogging.

Thanks Lynn, Staci and DIDISREAL for your very kind words and support. My hope is that NST is made visible and really tackled this century with true prevention happening. Won’t that be exciting! All the best to you all for your very important work as well.

For the ineffable energies, time, care, etc., we are grateful to you!

The validation means so much. Still, as memories push their way through the layers, the body grows more painful and gripped with another “mystery illness. ” We must let the next-generation aware/awakened to NST; to the early symptoms of dissociation so they can seek help b/f they abuse themselves–eating disorders, addictions (process incl.). ENDING THE VIOLENCE–is our hope….

You are so right Stacy. Breaking the cycle and ultimately getting to prevention is the goal. Thanks for your lovely words. And so sorry for your suffering.

THANK YOU, Linda. Not that we like suffering, especially the somatic symptoms which so few understand, but we aren’t sorry. One day, HOPEFULLY soon, we’ll be able to share our experiences with others who have been through the same or similar. We know that it’s not easy to trust others early on, especially those in positions of authority, but, as peers it’s less scary, less threatening to. So, our experiences may be invaluable. As a Certified Peer Specialist, and an alcoholic in long term recovery, we know that it works. (Of course, we mean in cases of this complexity, a peer’s role would be a part of a multi-disciplinary tx team!)

Again, your positive feedback is very much appreciated (:+}!

Thank you so much! The power of naming it and the validation! We are so overcome with gratitude!

Having NST named will eventually stop the discrimination and segregation of persons who have endured NST. Naming is a political act to change society. Thank you Joann. Jeanne and I are so very proud to help in any way we can. Sending you caring.

Stacy, I like Linda, am very sorry for the “body talk” memories that bring the cellular pain that was stored, unsafe to be expressed, but when safe, painfully safe, reveals the truth of what was once inflicted and suffered.

Linda and I are preparing to participate in three panels at the UN Commission on the Status of Women, all address torture perpetrated by private individuals/groups of non-State actors. Any way we can expose the reality is so worth the effort, as what has been endured is an unconscionable human right violation that must be named, acknowledged, exposed and stopped!!!!