For this first issue, as a means to further introduce you to Borne, we thought to offer you selections of our own work. -Eds.

Janet Thomas is an author, editor, playwright, and teacher. Over the last few years, she’s traveled to India to teach the art of memoir writing. Below is an excerpt of her 2011 Nautilus Award winning book.

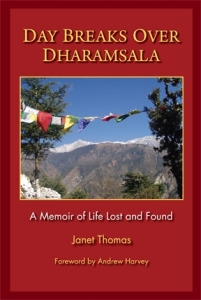

Day Breaks Over Dharamsala, A Memoir of Life Lost and Found

Day Breaks Over Dharamsala, A Memoir of Life Lost and Found

Chapter 10

For more than twenty years I have wrestled with, and been wrestled by, the truth. When I collapsed in the middle of my kitchen between Christmas and New Year’s, 1984, I had no idea that I was falling off the edge of my world. I had no idea that the inner framework of my life was imploding, and that the rest of my life would become a psychological reconstruction zone. The moment was visceral and paralyzing. I could no longer make my self up. But it would be years before I could even begin to describe what happened to me. And the way in to my truth was through lies.

The issues of mind control and medical experimentation, ritual abuse, Satanism, Nazi science, occult practice, child pornography—they all exist within a world of denial, and sometimes ridicule. Some of it is rooted in societal denial, some of it is professional denial from within the therapeutic community, and some of the denial, and the ridicule, is promulgated on purpose. The truth is—mind control, illegal medical experimentation, ritual abuse, Satanism, Nazi science, occult practice, and child pornography all exist. And they all exist within a world of lies. In many ways, the words themselves are lies because they are not experience. And this is a book about experience and those words have nothing to do with my experience, even as they were my experience. Because I was a child. A child to whom those words had no meaning.

As I recovered my memories, I began to recover my core self, the self that knew its own inherent being. I learned the truth because I began to recognize lies. And the biggest lie of all was that I did not have a self. It was a lie I was raised inside, a lie that left me without control, and a lie that was my truth. It was also a lie that saved my life. Because underneath the lie of my non-existent self, was another lie—that my self, should I choose to discover it, was bad. It was easier to live with a created good self that didn’t believe in the existence of hatred, abuse or evil than to face a self that was defiled. It was the lies I was told and the lies I told myself that became my truth.

Our minds are miraculous. We are all told how little of our brain we use, how much of it is a mystery, how much we don’t know about what we know. Our mind is perceived by us to be separate from our brain. Our mind uses our brain to create our reality. And along the way our senses come into play, giving us contact with the reality we can experience. The sight, sound, smell, touch and taste of things are what we know most intimately. They are experience; and we don’t have to make up our minds about what we experience.

But it is only in less evident ways that we “know” what we are told. We “make up our minds” about things we hear and read based upon what we think and believe. But there is a Buddhist bumper sticker that reads: “You don’t have to believe everything you think.” And its corollary is true: “You don’t have to think everything you believe.” My thoughts have fought to lay claim to my life, but it is what exists underneath my thoughts that saved my life. It was my faith that believed in me when I was unable to do so. A faith I had no words for. Just as I had no words for what happened to me.

“What happened to you, Janet? You used to be such a good girl.”

These are my mother’s words. And their significance became evident only 20 years after they were spoken. She said them to me out of the blue when I was somewhere in the midst of expressing enthusiasm for a play I was writing for the Empty Space Theater in Seattle. I was having some success, beginning a career. Her question startled me. But I did not ask “Why do you say that?” or “What do you mean?” Questions, I have come to realize, that are most normal. Instead, I let it slide by with a shrug of acceptance. I didn’t even know if she expected an answer. It seemed as though she was expressing a thought out loud and could not help herself. She looked at me curiously, as though she’d never seen me before. Perhaps it was then that I began to win the war I didn’t know I was waging.

It was during the year before my implosion. A year in which experiences with my father, too, took on an altered hue. During a massive ice and snow storm in the Northwest, he had successful heart surgery. I tromped through thick snow to visit him in the hospital. During one visit, a doctor came into his room and asked him if he was allergic to a certain medication. “I don’t know,” my father said. “I’ve never had any.” It turned out that he was.

An hour after I left, after receiving the medication to help him heal, he went into allergic shock and cardiac arrest. But he was in a hospital and the resuscitation team saved his life. And it changed his life. He had a near-death experience and the details of his journey out of his body, his experience looking down upon himself, watching himself be saved, and the nurse who comforted him as the shock paddles were administered, became the story of the rest of his life. He knew spring. He noticed flowers budding for the first time. He could smell the changing seasons and feel the new light returning. He was a changed man. A human man.

Throughout my life, I felt so much fear of my father that it was all I knew. And I knew nothing about him. He was formal, completely emotionally contained, and, from what I have observed in the lives of others, he knew no fatherly ways of being. He told us he was a Mason and that what he did was secret. He went out alone a lot in the evenings and never said where. He was a profoundly mysterious man whose only show of emotion was an agitated wringing of his hands, sometimes around the steering wheel of the car when he was driving. He had an eminent sense of himself. He was the authority in the family and he ruled through psychological intimidation. There were no bloody noses, just irreparable damage to heart, mind and soul. After his near-death experience, came signs of the human being; the father that never was suddenly had a second chance. It was his epiphany. But I was too far gone to take any comfort. It meant I would have to face that which was unknowable, unspeakable and un-faceable.

When I look back at this time from the vantage point of healing, I see the ways in which I was plunged into a profound psychological crisis. I suddenly had a father. Like my mother, but for different reasons, he, too, was seeing me for the first time—through the eyes of life. But there was no way for me to feel perceived through the eyes of life. I really was still “the good girl”—obedient, obliging, obligated—my servile role in the family intact. To be seen through the eyes of life meant to be seen in life, as alive, as free, as me. I had no reference point for this experience, no way to feel it, no way to know that it was even a feeling that could be had. It was an existential dilemma that I can write about now; but at the time I was a sitting existential duck. All of my life had been a lie. And that was the truth.

My parents had divorced years earlier in a frenzy of hatred and recrimination. I rallied to my mother’s side even as I understood the ways in which they should never be together. My father never spoke ill of my mother to me but he controlled her life in cruel ways by withholding financial support and treating her with dismissive disdain. My mother’s rage took on a wrath that would be impressive if it were not so destructive. We were not allowed to speak my father’s name nor even imply his existence. And if we were to slip up in this regard, as I did once at Thanksgiving when I asked one of my brothers if his new girlfriend had met our father, we were summarily tossed out and our stuff unceremoniously tossed out behind us. Months of rage and recrimination followed. But I remained at her beck and call. And I remained my father’s ally, too. Yes, he’s vile, I told her. Yes, she’s crazy, I told him. Their divorce didn’t change the ways they had never loved one another, or the ways in which neither I nor my brothers had ever been loved.

More than twenty years later, from both friends and acquaintances, I have learned what love looks like between parent and child. Even my own profound love for my son didn’t have the unconditional loyalty and dependability and safety that I see in familial relationships. Colin has forgiven me. Forgiving myself is far more complicated.

Satanism is a word that cannot be written without the corresponding language of urban myth, science fiction, Salem witch trials and false memory syndrome co-opting its reality. But Satanism is a real thing. It’s considered a religion—allowed in prisons, disallowed on the tax rolls, taught in colleges, and given legitimate standing in courts of law. When I speak the word, I hear its artifice. Yet I fight against its nihilism, its degradation, its sour derision about all that carries grace in this world. It is a battle I win, and lose, every day.

The weaving together of cult-trained children, medical experimentation, and criminal activity is nothing new. And it’s very easy to hide. A child, whose mind has been extracted, manipulated and de-personalized through drugs, electric shocks, sensory deprivation, and other forms of manipulation, can be trained to forget. And then trained to forget that she has forgotten. For me, this meant that having no memory was a natural state. And because we moved so much and I was continually isolated from having friends, or knowing even geographic constancy, I was unmoored even from the physical links of continuity that give ready reference to a life.

“What happened to you, Janet?” It is a question I am asked and, often pointedly, not asked. It is a question I answer and don’t answer. In theatre there is the phrase, “suspension of disbelief.” It invites us to enter an unreal world and experience it as reality. It is what I am listening for when, “What happened to you?” is asked, or not asked. Because answering it requires words to come out of my mouth. And when they do, I, too, have to face the truth. I have to face the fear, the disbelief, and that strange stone self inside me who can neither speak nor know she is alive. To remember what happened to me is to remember dying.

It is what I know and don’t have to remember that gives foundation to all that I have remembered. Electric shocks were always part of my vocabulary. I had shocks often because I heard those words when I was very small and I knew that’s where I was going. They said it was because of my arm. I had my photograph taken often. I know because I know I went there. Knowing things and remembering things are different. I know I had electric shocks; I didn’t remember having them. I know I had my picture taken without my clothes on and I felt the painful intrusion into my body; I just didn’t remember the actual sexual acts of my five-year-old self. Forgetting them was part of the shock treatment. Electric shocks eliminate the memory of electric shocks. They also eliminate the memory of self and experience. But trauma rests in the body and in the psyche. It neither forgets nor does it get forgotten. It plays out its truth as though suspended timelessly inside the body—still happening. Trauma, hidden from memory, must be remembered by the body and acknowledged with the greatest of respect by the mind and tenderness by the emotional self; or it runs roughshod over a life. Its causes are either uncovered or trauma goes about perpetrating itself even more upon others as well as upon the suffering self. It took the Vietnam War to put post-traumatic stress disorder into everyday vocabulary, but it was already a reality to untold millions of victims of violence throughout history.

The professionals only get it right after the fact. From the vantage point of healing I know how it feels to have a self and I can compare it to no-self. The feeling of no-self is a disarray of disconnected moments. Self is connection, continuity and commonplace. It is, therefore it will be. And it is everywhere all at once and forever a web of both pleasure and pain. No-self has no connections to anything but a precarious and unsettling fear.

The weirdness about healing is that the self who went into hiding, the core of me, did not have these experiences of life. It meant, also, that I did not have her. In healing, she has a place to come to. In her, I have a place to go. The journey between these two places is convoluted and complex. It will always make me a liar to someone.

But in the realm of mind control, illegal medical experimentation, ritual abuse, Satanism, Nazi science, occult practice, and child pornography there’s plenty enough to believe and not-believe—for everyone. The facts are in: Nazi scientists were brought to Great Britain, the U.S. and Canada after the war and their work with human experimentation as well as nuclear science was utilized. Mind-control experimentation is well documented. In 1988, the CIA settled the lawsuit filed by Canadian victims after years of mind-control experimentation by CIA-funded programs run by Ewen Cameron in Montreal. He was a Scottish psychiatrist who lived in the U.S. but ran his mind-control research through the Allan Memorial Institute, which was, and is, part of McGill University. There is enough evidence of online child-pornography to satisfy the most skeptical of Pollyanna’s. And those children are real. They are not photographs. They are innocent victims, stolen and sold, sometimes by their parents. They are subjected to sex in vile and painful ways. They are photographed. They make millions, perhaps billions, of dollars for their perpetrators. As children, their bodies and faces change and grow. They are not easily identified. They live next door to you. And so do their perpetrators.

Satanism exists. Googling the word brings up more than a million links. Some of them are simply Goth-like sites dedicated to adolescent rebellion. Others link to the Church of Satan established in the U.S. by Anton LeVey and celebrated by the likes of Colonel Michael Aquino who used to run daycare centers throughout the U.S. Army. Other links take you to the occult and the history of the metaphysics of Satanism. Hitler was an occultist and a Satanist. He believed in controlling the human mind and overpowering the human spirit. And he was successful. And his legacy is still at work. It is our denial that will do us in. Believing in that which does not believe in us is essential to our survival as human beings. We have to know what we are up against.

In her thoroughly researched and award-winning book, In the Sleep Room—The Story of the CIA Brainwashing Experiments in Canada, journalist Anne Collins maps out the landscape of Cold War paranoia that led to the expansion of official mind-control experimentation. She writes about Allen Dulles, who was to become director of the CIA in the fifties and “was in Switzerland and Germany recruiting fascist intelligence agents for the new war against communism before the old war was over.”

I am often in denial as much as the person I tell my story to who thinks all this mind control business is the stuff of science fiction. But it’s not. And there are heroes to prove it.

If you go to the official Presidential Medal of Freedom website you can find recipient Joseph L. Rauh Jr., who was awarded the Medal of Freedom on November 30, 1993, by President Bill Clinton. The letter recommending Joe Rauh Jr., was signed by such notables as: Justice William Brennan, Vernon Jordan, Eleanor Holmes Norton, Frank Coffin, Judith Lichtman, Arthur Miller, Thomas Eagleton, Marian Wright Edelman, John Kenneth Galbraith, Katherine Graham, Senator Edward Kennedy, Benjamin L. Hooks, Ralph Neas, Arthur Schlessinger, Jr., Senator Paul Simon, William Taylor, Roger Wilkins and Coretta Scott King. The letter of recommendation is important for two reasons: for what it includes and for what it doesn’t include.

“We are writing this letter to recommend that the Medal of Freedom be awarded posthumously to Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., the foremost civil rights and civil liberties lawyer of our time. Joe Rauh died on September 3, 1992, at the age of 81. For more than half a century, he devoted his life to the fulfillment of the Constitution’s great promise of equal justice and freedom for all. No one has ever fought harder or longer for the rights of minorities, the disadvantaged and the underdog.”

The letter continues in pages of laudatory prose about Joseph Rauh’s lifetime of work in the public interest. What it leaves out is Joseph Rauh’s last great public interest case—a lawsuit against the CIA on behalf of a group of unsuspecting Canadians who were used as guinea pigs in CIA-funded brainwashing experiments at a Montreal psychiatric hospital.

It was an eight year-long lawsuit on behalf of nine plaintiffs that was settled out-of-court in 1988. They each received $100,000, and later, 76 other people received $100,000 each from the Canadian government, which, along with the CIA, had funded Cameron’s work. It all happened behind the looming grey walls of Ravenscrag, the mansion that once belonged to shipping magnate Sir Hugh Allan and eventually became the Allan Memorial Institute. Ewen Cameron eventually became president of the Quebec Psychiatric Association, the Canadian Psychiatric Association, the American Psychiatric Association, the World Psychiatric Association and the Association for Biological Psychiatry.

Under Cameron and his colleagues’ experiments, patients were subjected to an onslaught of drug cocktails and injections—including LSD—that left them in states of terror, disoriented in mind and body and amnesic regarding who they were, where they belonged, and who belonged there with them. Add to the mix electroshock therapy that far exceeded the normal voltage and frequency, and drug-induced brainwashing comas for days at a time. The results are easy, and horrifying, to imagine. That apparently was not of concern to the researchers who more than anything wanted to break the code of the human mind. They wanted to know how to erase memory and rebuild the psyche. They wanted to learn what the mind could be made to do, and not do. It was, and still is, the ultimate challenge in some scientific circles. When it comes to power, prestige, money, or all of the above, being a human-being sometimes doesn’t matter much.

But it mattered to Joseph L. Rauh, Jr. He is a hero to those of us who cannot speak out for ourselves, cannot fight for ourselves, and cannot even name our fears for ourselves. Drugs and electric shock wipes out memory of life and memory of self. It does this thoroughly and it did it to me. But the self has a memory deeper than we can remember. It is a self that remembers us. It is that place in us that can neither be created nor destroyed. It goes into hiding but it does not die. Even though it sometimes feels like it.

As is often the case when things are claimed true by so-called “experts” who make money from them, the effects of electroshock treatments have been historically minimized. But in January, 2007, the nation’s top electro-shock researcher, Harold Sackheim of Columbia University, who had long claimed that the electroshock treatment doesn’t cause damage, repudiated his own 25 year-long claim. The man who taught a generation of electro-shock practitioners that permanent amnesia from ECT is so rare that it could not be studied announced that it “causes permanent amnesia and permanent deficits in cognitive abilities, which affect individuals’ ability to function.”

What also came to light was Sackheim’s role for more than 20 years as a consultant to the electro-shock device manufacturer Mecta Corp.

After Sackheim repudiated his own life’s work, Linda Andre, head of the Committee for Truth in Psychiatry, a national organization of electro-shock recipients, said, “Those patients who reported permanent adverse effects on cognition have now had their experiences validated.” Amen. The National Institute of Mental Health estimates that more than 3 million people have received electro-shock over the past generation.

This stuff fuels my rage. Expert information is too often attached to somebody’s massive ego or revered bank account—usually both. It’s why Joseph Rauh, Jr., deserves to be known, revered and remembered for his last case—the one overlooked by history.

Rauh’s partner in the lawsuit against the CIA, James C. Turner, spoke about Rauh at the inauguration of the District of Columbia’s public law school, along with a showing of the Canadian Broadcasting Company film based on “The Sleep Room.” Here’s an excerpt from Turner’s talk:

No one knows how many hundreds of patients were abused in these CIA experiments, but the people we represented had their health devastated and their lives shattered by these bizarre experiments – all conducted without any patient knowledge or consent in violation of the code for medical ethics our country enforced at the Nuremburg War Crime Trials.

Joe was outraged at this story of how the CIA abused its power to conduct secret operations, and believed that accountability for this misconduct was critical. In a word, this was a public interest fight for the principle that no part of our government is above the law. We also believed that reasserting this principle was especially important in the 1980s with the emergence of an increasingly out-of-control CIA led by its then Director, William Casey.

‘The Sleep Room’ captures the essence of a public interest fight, as well as Joe Rauh’s personal humanity to all those who knew and worked with him. It also documents Joe’s incredible determination and fortitude – for those of us who knew and worked with him have no doubt that the CIA’s decade long strategy of litigation by attrition cost Joe his health and ultimately shortened his life.

You won’t find any of this information about Joseph Rauh, Jr. on “The Official Site of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.” Nor are you likely to find much in any mainstream media. But mind control, illegal medical experimentation, ritual abuse, Satanism, Nazi science, occult practice, and child pornography – all these things exist. And in my personal experience, they are all related.

I was born in Wales at the end of the Second World War. I was born into a family in which my father—and his wealthy English father—prevailed within the throes of Nazi sympathizing and admiration. This was not uncommon in England. Years later I would recognize it in the tone of my father who spoke about Winston Churchill with derisive respect. It was as though the victory over Nazism was an accident, a mistake.

During the war, my father was a munitions inspector who traveled throughout England and Wales. He was from a wealthy English family. He met my mother, the oldest of six children in a working-class Welsh family, in the course of his work. “Your mother got us into something she shouldn’t have,” was a refrain of my father’s. For many years I heard this as a lie. He was far too powerful and frightening to be coerced by my mother into anything. But as the course of my separation from my parents unwound its way through my life, my mother took on greater and darker shadow. And over the course of years, as the pieces of my past fit inexorably into place, I found out that she had a cold manipulative mind long before she met my father. Perhaps she did lead the way into their secret life. But perhaps they met through it, each of them already vowing allegiance to the unnatural, the place where love is mocked and the power of mockery worshipped. The bond between me and my mother has no echo in my memory.

I was a bright and beautiful expendable little girl. It was easy to exploit me in child pornography and prostitution. I have remembered this in ways that are far too graphic to write about. Then, when I was five-years-old, and already psychologically fragmented—both on purpose and for the sake of my own survival—I was used in medical experimentation. I was told I had polio. I was whisked away in an ambulance with dark windows. It seemed as though I was more often in clinical environments than I was at home. I don’t, in fact, ever remember being at home in England. I remember clinics, hospitals, ether and fear. And there was some kind of a school where we slept in rows and weren’t allowed to use more than one square of toilet paper. There were terrible smells. And there was a photo studio. And once I remember falling off a swing on purpose and asking a young boy to walk me home. Why was I alone in the park? Why did I fall off the swing on purpose? What happened to the little boy after I took him home? Where was home?

When I was five years old, my arm was cut open and the nerve serving my left hand was severed. I was taken from the school “three times a week for a year” (these words echo from my childhood memory) to receive electric shock treatment, perhaps to see if the nerve would grow. Perhaps to eliminate the memory of my sexual exploitation. Perhaps to have personalities implanted through intimidation and terror and “the good girl” put in the place of the self that might remember. My thumb and forefinger are half the size of those on my right hand. My thumb doesn’t bend. There’s very little feeling in my left hand and it does not grasp. All my writing is done by two fingers on my right hand. Throughout my life I adjusted to my numb and helpless five-year-old fingers the way I adjusted to my numb and helpless five-year-old self—by pretending they weren’t there.

I was seven years-old when we moved to Montreal, where we lived in three different houses over the next five years. I remember where they were. I just don’t remember being inside them with my family. Once again, I was “sent places” to “see people.” I was “special.” Sometimes people came to see me in the large closet up in the attic, where there was a mattress. I was sent to drama classes in the basement of an old church, where I wore a lot of make-up and pleased people. I was sent into the city by myself on the train to see a “mind doctor;” and next door to one of the houses in which we lived there was a couple who were “mind doctors.” It is the clinical places that are familiar to memory—and the clinical people. I don’t remember where I slept at home, where I played with my brothers, where I ate meals, or where anything was in my world. Was I subjected to the drug induced sleep and de-patterning programs perpetrated by Dr. Ewen Cameron? I don’t know where it was I was sent. I do know that the Allan Memorial Institute has resonance in my past. And that in Montreal, I was subjected to massive electric shock treatments and ongoing exploitation. I do know that “doctors and nurses” were involved—scary people wearing white coats, in my child memory. As I look back with the language of my adulthood, I recognize that I was always more of an experiment than somebody’s child. There were mirrors that were windows, always appointments to keep, and extended times when I was sent away. I recognize a child in shock, a child trained to perform sexually and otherwise, a child arousing continual clinical curiosity and observation, a child who could see through it all and could do nothing about it.

After five years in Montreal, we took a ship back to England for the summer. I was twelve years old and I remember a yellow cardigan “twin-set” that my grandfather bought me. He was my father’s father, the one who owned both a toy store and a brass factory. Once, when we were in Montreal, he came to visit us and had my father take a photo of him in front of somebody else’s fancy mansion so he could show it to his friends as the house his son bought. He was jovial and frightening. His own house, grand and formal, had rooms that were rarely entered. Like everything else in my life, the trip that summer is lost to a fugue in which there is no memory of place or of people. Only the fresh air of being on the high seas and the freedom of being outside tells me I went.

When we came back from that summer visit to England, instead of going home to Montreal, we moved straight to Vancouver where my father had yet another new job as an engineer. This was a shock. It was also where my life as I know it began. Not in the first Vancouver neighborhood, where I know we lived because I went to school there and remember its name. It was in the second house, the one in North Vancouver, where I remember where I slept. It is there where the first experience of being takes shape in my memory. I was thirteen. This is not unusual in survivors; we are saved by puberty partly because our exploitation could make us pregnant, and partly because our lives grow more external and less controllable. I remember friends and parties and boyfriends and hikes and French fries after school. I had my own room. I looked after my brothers and was a surrogate mom to a new baby brother, who thought later in his life that perhaps I was his mother. Because I loved him.

What little I knew of human love was as a big sister. When, at the age of 41, I made a decision to suspend relationship with my parents, I lost my brothers. This was the real loss. That my parents didn’t or couldn’t love me I had experienced my whole life. But I had counted on my four brothers. After years of healing, I understand how the family system abandoned them, too. As well as how it replicated itself.

The “training” I experienced was to eliminate “the self” and replace it with artificially created parts, or personalities that could perform accordingly in sexual ways, and always obediently in other ways. Electric shock was the primary tool. But there were other states, too, that leaked through in to my later life. Lying for hours, dead-still, staring at the ceiling, knowing neither time nor space is a life-long experience resulting from sensory deprivation and drug treatments. I didn’t recognize this as unusual until it stopped happening as much. It is still a place I can slip into too easily. Not being able to talk, to say what I mean, think, or feel was my life for nearly fifty years. The great irony here is that although I was not allowed to speak for myself, to ask for anything, or to name myself in any way, nobody ever told me I couldn’t write. In one way or another I leaked out in my writing and I claimed my life through my writing. Books were miracles because they were written. The writer did not have to exist.

The writing part of my life must have been an immense shock to my family. At the time I didn’t recognize this because I was long used to being invisible and did not know how to expect recognition from within the family. My ability to give language to the characters in my plays was an immense irony when I could not give language to myself—or as it would turn out—my selves. Perhaps it was the first sign that all had not gone as planned.

This mind-control business is not big news. Getting control over the mind has been, and still is, a juicy goal for everyone from neuroscientists to military experts to dictators to marketing consultants. They are all out there, and in the back of this book there are many legitimate resources listed for those interested in educating themselves about these issues. Kids indoctrinated into cults and their perverted money-making schemes are great resources for mind-control experimentation because they have already been trained not to exist. Kids in general are great resources because they are helpless, available, and malleable. In less hidden ways, the flagrant international child sex-slave and sex-trade business—an epidemic of it—is thriving barely underground. Incest and child sexual abuse are words that have only become acceptable over the past 20 years, but their reality is part of age-old abuse. It might take another 20 years for the survivors of mind-control experimentation and its attendant abuses to become household words, but we will. And I do not stand alone.

There are thousands of us scattered throughout North America, tens of thousands of us around the world. Some of us are lucky enough to find one another. Within my very small island community I know two other survivors of mind and sexual abuse who struggle every day to find their way into being. They are accomplished, respected people who keep private the circumstances of their past and their struggle. The culture of denial does not welcome disclosure, does not welcome the grief, the isolation, the need to be seen and to be recognized that is at the very core of our experience. So we reinforce our insularity through our competence, our skillful means of dissociating, and our need to somehow in some way appear “normal.”

Some of our stories begin in our families when we are born, some of them happen later at the hands of outsiders. Some of our stories are part of “official” programs; others stay beholden to illegal greed and exploitation.

There are many stories in my life that defy belief. The man I married, who, from a later perspective, appeared to have been placed in my life on purpose. My infant son who died suddenly and mysteriously, giving rise years later to the possibility that he did not die but was taken. The people who seemed to come into my life by accident but didn’t; my continual self-sabotaging; the sabotaging by others; the extent and depth of what I don’t remember about my life; the way memories surfaced without context of time and place; the way fear defined my very existence. It was only when fear was not my basic frame of reference that I began to realize it had been my entire life. By then I was in my fifties. All the ways in which I had no choice in my life are also difficult to comprehend as well as difficult to believe. They are as difficult to believe as the ways in which I was continually saved from death and despair by circumstances of divine intervention and protection, by grace.

Grace has always intervened in decisive ways, introducing me to painters and poets, to books that call to me from a shelf, to places and jobs, to my therapist, to my spiritual teachers and to people who became my friends and helped love me into being. My inability to plan a life for myself left nothing but grace in its wake. Everything—from Buddhism to Christianity to where I live and to how I got here to India—is evidence of grace. It’s with me even when I am unable to be with it.

Every day I doubt the experiences of my childhood. And every day I know they were true. And every day here in Dharamsala is a massive confirmation. Because everywhere I go I am surrounded and encountered by self. No matter how limited and challenged are the lives of those around me, their expression of self-ness is loudly and visibly apparent. It is an innocent, unconscious and unquestioned self-ness. Back home, in the world in which I live, deep self-ness is masked by the cultural self, the accomplishing self, the social self, the self that shows up for special occasions. They are masks that call out my own. But here, in India, it is the unencumbered self that calls out my own and tells me I am home.

Free will is an extraordinarily subtle experience. It is an experience I continue to learn to have and I expect to be doing so for the rest of my life. Most of all, it is a feeling that rests in the body. To want something—whether it is to take a nap, a vacation or a bike ride—is simple, and seems to rise easily in people. Whether they get what it is they want doesn’t get in the way of the wanting. But I was trained not to want. Wanting something automatically and immediately put it out of the realm of possibility. And when I was actually offered something I wanted, like an ice cream cone, if I expressed wanting a certain flavor, like chocolate, I was not allowed to have any ice cream at all. I was punished for wanting, which meant that the feeling of wanting was the very thing that destroyed the possibility of having. The convolutions around this predicament continue to be a challenge, even all these years into healing. To want something still carries with it the knowledge that I can’t have it—whether it’s a love affair or a stick of licorice. I was trained to be obedient to the will of others and to never, ever want something. How this played out in my life, from my servitude within my family to the ways in which I capitulated to the needs of others in my adult life—particularly when it came to sex—is a realm of shame and humiliation.

It is profoundly ironic, that at the age of forty, when love took me down, it wasn’t a broken heart that first got me into therapy with Brian. It was the real and present promise of my own passion that I could not face. When my passion surfaced for its first pure view of the world it presented me with the perversion in my life. I didn’t know these words back then. I knew racking, irreconcilable grieving. Falling in love and being loved back with passion and pleasure derailed me completely. The conditioning of my mind had completely kept my past at bay; but when, through layers of denial and amnesia, passionate love surfaced in my body, it plunged me into complete breakdown.

In therapy I came to memory in odd and unaccountable ways, many of them through abiding grief. It was the way I “knew” things. And I knew them through my child’s body, through people being around me watching me in fascination, through circumstances of sex and exposure that made no sense. It all felt so organized, so purposeful. I could not understand it. There was a context missing and it was driving me crazy. I was a year and a half into therapy and over my head in unending grief and paralyzing fear when I was driven in frustration to the Seattle Public Library one day. I looked up organized child abuse in England in the card catalog. There was no Google in those days, no way to make it easy. When I saw the words “ritual abuse” my whole body went cold with recognition. What I had remembered was not crazy. I was not crazy.

When I got to Brian’s office that afternoon in the spring of 1986, I sat on the couch and I said those two words. “Ritual abuse.” He was very quiet and tears came into his eyes. He opened his appointment book and showed me a small yellow square sticky note. “Suspect cult abuse with Janet. Should I tell her?” I was the topic of his discussion with peers. What to do about me?

Years unfolded. Therapy, body work, retreat, isolation, greater and greater grief, shame, belief and disbelief—it was a slow and inexorable facing up to the truth. Brian learned along with me. He never, ever, put words in my mouth. Even now, all these years later, it is only when I ask him for information that he offers any. His commitment is always to my healing. To helping me unfold into the mystery of the life that is rightfully mine.

He told me how people reveal their truth. “It’s like a puzzle,” he said. “Different pieces are turned over, and at first they are connected in unidentifiable clumps. Soon parts of the picture begin to make sense, and then, finally, the big picture. And some people put the whole puzzle together face down. Only when they decide to turn it over and look at it does it makes sense.” It’s this last description that resonates with me. I had to reconnect to and rebuild my self before I could face the facts and the fantasies of my life. I could not name my past until I had named myself.

“How will I recognize when I’m feeling my core self?” I asked Brian. He laughed. “Because it’s so comfortable there’s no question about it.” He said it feels comfortable precisely because there’s nothing to feel. It simply is. And he is right.

The road to recovery is a complicated trek but the destination is simple: to simply be. When we get there, it is heaven. The most normal moments are transcendent. Waking up and getting out of bed without thinking about it is a miraculous moment. So is looking into the eyes of another without feeling shame, or playing spontaneously with a child without feeling a blight of self-consciousness, or walking down a crowded sidewalk without feeling alien. It is the place inside us that cannot be named that is targeted by those who think it can be destroyed. They, however, are wrong. The spirit has an invincible vocabulary of its own. All these methods of abuse, no matter how brutal or “scientific,” cannot kill the human spirit.

Janet, this is so profoundly powerful, honest, moving, and intimate. Thank you so much for sharing your journey of discovery of the self and the wholeness of it that most of us take for granted. It adds depth and perspective to my own life just to know you.